Cast your net wide

Are you overlooking an important way to improve your research?

There are lots of ways to strengthen your research, whether it's keeping an open mind, taking advantage of library resources, or developing a robust system for information management.

But one that sometimes gets overlooked is the value that simply comes from talking to people outside your field and listening to what they have to say. We spoke to three early-career researchers about the difference this made to their own research.

For Hollie Booth, a PhD student at the University of Oxford’s Interdisciplinary Centre for Conservation Science (ICCS), research involves examining socio-economic drivers in fishing and considering socio-psychological factors in Indonesia.

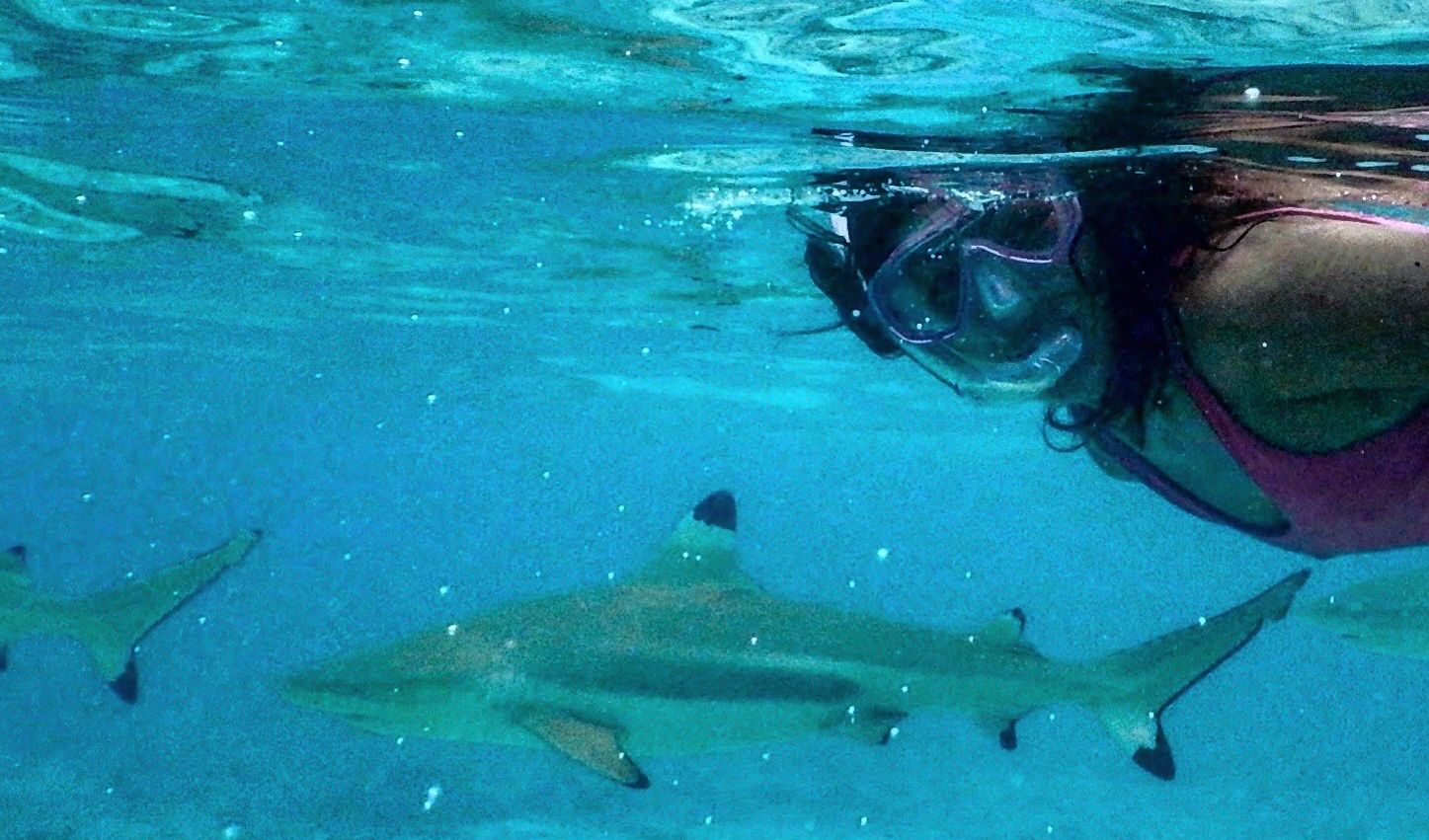

Every now and then, her research also involves swimming with sharks

Hollie has spent her research career living around the world, from managing wildlife in Tanzania to exploring shark conservation in Indonesia.

Her recent study, The neglected complexities of shark fisheries, and priorities for holistic risk-based management, published in the Elsevier journal Ocean & Coastal Management (Dec 2019), looks at developing feasible, cost-effective management strategies for endangered sharks.

"Sharks are one of the world’s most threatened species groups, mainly due to over-fishing," she explained.

"However, relatively little research has focused on the socio-economic and behavioural drivers of shark fishing. As such, technologies and practices that reduce fisheries’ impacts on sharks are relatively well documented, yet less is known about how to encourage their adoption."

Where the majority of research around shark conservation focuses on bio-physical and technical aspects of shark species and fisheries, Hollie's research enters another realm. She drew on her three years of practical experiences working on shark and ray conservation in small-scale fisheries in Indonesia.

"After visiting several fisheries and speaking to many small-scale fishers, I realised that shark conservation efforts would not be successful without considering the needs and experiences of ocean-dependent people.

"As such, our research highlights the importance of considering socio-economic factors when conducting fishery risk assessments and designing management measures for shark conservation. For example, we highlighted that flawed assumptions about fisher motivations and capacities, and a failure to consider local socio-psychological factors such as social networks and cultural drivers, can result in unsuccessful conservation interventions. In Indonesia, many shark fishers inherit their gear and fishing practices from their fathers and grandfathers and therefore have pride in their way of life.

"These considerations mean that some mandated shark management measures may violate social and cultural norms, leading to widespread non-compliance.

"We also wanted to emphasise that given the scale of shark conservation problems, and pressures from multiple fisheries, tailored solutions to conservation need to be adopted at scale. They also need to be integrated into national-level plans rather than through piecemeal projects to have a greater impact."

Hollie hopes the paper will inspire and provide a robust scientific basis for researchers, managers and policymakers to adopt more interdisciplinary approaches to shark conservation, which can ultimately produce better conservation outcomes for sharks, alongside well-being outcomes for coastal communities.

Read more from Hollie

Like Hollie, Rodrigo Oyanedel of the University of Oxford Department of Zoology also spent time with fishers across the world, in his case from Chile to the Philippines. Listening to their challenges, daily life experiences and motivations has informed the work he does studying the relationship between ocean conservation and the way people interact with the ocean’s resources.

"We're bringing together different theoretical perspectives and lines of evidence."

Rodrigo explained how his working experiences as consultant in Chile informed his research topic:

"I realised that the major driver of exploitation in the ocean was illegal fishing, and I was frustrated by the lack of evidence to solve the problem. I decided to undertake my PhD to try to better understand the wildlife trade from a broader perspective. Previous research had looked at isolated components of wildlife markets, hindering our ability to intervene effectively and improve sustainability."

Instead Rodrigo's work, published in the Elsevier journal Science of the Total Environment proposed a new framework for assessing and intervening in wildlife markets – one that would look at different analytic levels of the wildlife trade, accounting for the complexity of such markets and the different dynamics driving them.

However, bringing the fishers into the project was not without its challenges. Rodrigo explained,

"As we started this project, we realised that a lot of the trade is concentrated in illegal markets, which can be very difficult to gain access to as an outsider. Due to the sometimes cryptic or illegal nature of these markets, many people did not want to speak to us for fear of repercussions, which made it more difficult to collect first-hand information and insight."

Nonetheless, by building trust Rodrigo and his team were able to work with the local communities to build a new framework for examining the wildlife trade. He explained:

"Our framework looked at three different levels in the wildlife trade: actors, inter-actors, and the market as a whole. At the first level, we assessed the underlying motives and mechanisms that enable or prevent different actors from benefitting from wildlife markets. For inter-actors, we focused on supply chain structure and the competition between those involved in the markets. Lastly, we evaluated supply-demand dynamics, quantity and price determinants, and the impact of illegal products flowing into markets."

These findings allow for a more concerted approach to understanding wildlife markets by bringing together different theoretical perspectives and lines of evidence. As Rodrigo explained:

"To conserve biodiversity, we need to have a strong understanding of how markets drive unsustainable wildlife use. Our work can help managers in different parts of the world to better identify interventions for improving the sustainability of such markets.

"Similarly, the framework can also help to prompt new ways of thinking about how best to intervene, by expanding the toolkit of available options and integrating diverse theoretical perspectives."

The importance of reaching across boundaries had a huge impact for Chemical and biomedical engineer Prof Cathy (Hua) Ye, an Associate Professor of Engineering Science at the University of Oxford and Director of the Oxford Centre for Tissue Engineering and Bioprocessing (OCTEB). Her recent research focused on a bioreactor. This is a vessel that aids a biological reaction (such as) cell proliferation, is a crucial component in developing stem cell therapies. In stem cell therapies and regenerative medicines, different types of cells are used for developing different therapies.

For Cathy, it was working across multiple disciplines and listening to other researchers that allowed her work to take shape:

"Cell therapy and tissue engineering is incredibly interdisciplinary, I’m not a cell biologist or clinician, so I needed to understand more beyond my own discipline, as did my team."

"The process requires commitment, dedication and good communication and collaboration between teams.

— Prof Cathy (Hua) Ye, BEng DPhil

That need for interdisciplinary communication extends throughout the project:

"There are also broader challenges to consider when creating tissues to replace diseased ones, also known as regenerative medicine.

"Clinicians set the initial problem; cell biologists then tell us which cells to use and their preferred growth environment, and we then think about a way to provide and maintain the environment for cells. Some of these can be ways to maintain nutrient supply to tissues grown outside human body without blood capillary network, and also deciding which cells to use, whether a patient’s own cells or donated cells, which both have pros and cons."

The work done by Cathy and her team enables large-scale cell growth to provide the best quality cells more efficiently and cost-effectively. This means it can play a role in medical research and clinical trials to help find cures for diseases.